Science at the Edge of the World

I decided to change my own mind about evolution in my freshman year of college, which is common: college is often the time and place where non-evolutionists grapple with whether we will become evolutionists.

I am comfortable telling people that I used to not believe in evolution – enthusiastic, even. A lot of things have made me very different from most of the people around me in both tech and STEM. This is one I decided to lean into, because some demon in me thinks it is very funny how much it scares tenured never-taught-in-public-school academic types.

There were a lot of things that I believed as a child that I still think were right. I honestly can't explain how I resisted the prevailing stories around me long enough to figure so many ideas out (people’s right to healthcare, the idea that women should get to go to college as much as anyone else, the very daring notion that a person could listen to pop music and not lose their soul). But evolution was not one of them. I didn't reason it out.

People imagine this kind of stuff badly; like there was a seminar-level debate about it and a moment you failed to see through the bullshit, like the obviousness of evolution must be present for a child who’s never had it explained to them. But try to remember being eight. Try to imagine hundreds of small probing questions as bids for attention and openness, rejected. Imagine being eight years old and wanting, quite badly, to believe in dinosaurs. Imagine the adults around you saying, with indulgent smiles: and do you believe in dragons too? Fairies? Imagine that slicing through your thoughts and the hot embarrassment crawling up your neck. Imagine getting half-answers, wrapped in fear: God made the world but the devil broke in. Did you know millions of people died in world war two? That was the devil’s work. You think he couldn’t fake a few bones? Do you really think scientists are right about everything? People have agendas. Imagine being thirteen and asking about biology and being told that to stray too far into the workings of cells was to invite the devil in (couldn’t sneeze without alerting that guy, he was everywhere). Trapdoors underneath every curiosity that all led back to the same pit. You are allowed to watch Jurassic Park, but you’re not allowed to believe in it, because that would be stupid.

So yeah. I missed out on evolution. When I think back on it I think less about this like a static belief than I think about it like static in my head, noisy confusion.

In my defense, the information I received on this was not just disinformation about the facts of bones and biology. It was also chaotic, disjointed, and high threat: believing in evolution wasn’t really about the belief itself, it was also about the fact that if you stepped out of line with regard to creation myths you would face the consequences. I intuited pretty early and hard that those consequences ranged from contempt, arguments, mockery, and the loss of the positive regard of the only people I had to talk to, to other more serious outcomes that lurked in the dark recesses of my mind, like going to hell.

Unfortunately for the heavenly agenda I was a fast learner. So when I got to college with my own evolving brain and a badly-packed suitcase, it only took one very awkward conversation for me to decide that not everybody had been taught what I had been taught. I went to the library to learn how to question everything. I did this badly and inefficiently: pulling down books from a science section, reading sections and chapters at a time. It was perhaps as much cultural learning than factual learning. A lot of paying attention to what was taken for granted. A lot of asking myself why people were so angry about it. What they were getting. How that was useful to them. Piece by piece, I learned a lot of new things and corrected bad misconceptions.

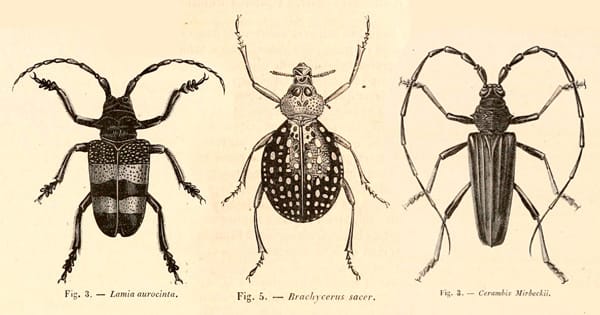

From this you may be assuming that I didn’t know anything about science, but I did. I knew how to name trees and the constellations of different flora and fauna that lived on the property I grew up on. I had a well-loved copy of a book called Botany for Gardeners and I was fascinated by it. I found the safest parts of science and loved them, from a distance, through the prism of the things I felt allowed to believe in: human beings exploring things, tangible and observable artifacts. As a sixteen year old I read Fabre. I used to go to a local bookstore and sit at the world atlas and look at the small font sections for each country that listed a few major plants and animals, and look at the map, and see where they might have traveled. This, I reasoned, was surely relatively inaccessible to the devil because it was history.

In the multiple pillars of literacy that help people combat misinformation, misinformation scholar and sociologist Matthew Facciani describes psychological, media, and scientific literacy as various dimensions we can use to protect our heads from the onslaught of misinformation in the world (I also recommend his fascinating work on the public communication of science. In this paper's conclusion: "For science to inform individual and collective decision-making, it is essential that people have access to science-related information and opportunities to participate in public discussions on science-related matters in private and public life.").

As you might imagine, I remain fascinated by the psychological dimension, including the ways that identity biases shape our intake of stories, both with and without our knowledge. I believe that as much as my childhood was full of that misinformation, it was also full of something else. It was full of me, and what I wanted, and the identities that I shaped for myself. Because I wasn’t in school, I was outside. I could look at the insects and wonder how these alien lifeforms, so different from me, coordinated and attempted to survive. I could watch the fruit trees in our orchard change and shed and flourish. I could literally see life, development to death, and I could see that there were countless versions of it on the planet. This created a very different trapdoor in my mind, secretly: I was a person who believed that diversity was a beautiful and a real thing and that we needed to understand it if we wanted to understand the world. And I wanted, very badly, to understand the world. This became an identity for me, being a learner, something that I still cherish and see as more central to myself than almost anything else.

At parties now, with my biology faculty partner’s biology faculty colleagues who describe students who show up to their classes with tellingly pointed questions about the fossil record, I like to drop this I didn’t believe in evolution thing in to see what happens. Usually people are interested and it’s an interesting thing to talk about. Sometimes I worry that scientists will think I’m stupid, because a lot of scientists think that being taught pseudoscience means you’re stupid. I suppose I have just traded one set of social consequences for the other, but I find these ones safer on average.

However, I know that I was not stupid just because I was raised with pseudoscience in my head. To identify as a learner is to believe that what matters is how you change, not what you were born into. I am grateful to that brave college student – it was brave just to go to college. It was a brave thing to believe that change was possible and even admirable. One of the biology faculty members I spoke to about this once said something I found incredibly sticky. I’ve returned to it again and again, because it changed one of my beliefs about how we might reach people. She said that when she teaches evolution to non-evolutionists who, like me, are grappling with being confronted in their views during their first years of college, she starts with why it’s useful. Evolution is fundamentally incredibly useful to us as a theory. It lets us explain so many of the things we see better than other theories. It coheres the evidence, like a good theory should. It does not stop your questions or try to suffocate them. It takes them seriously.

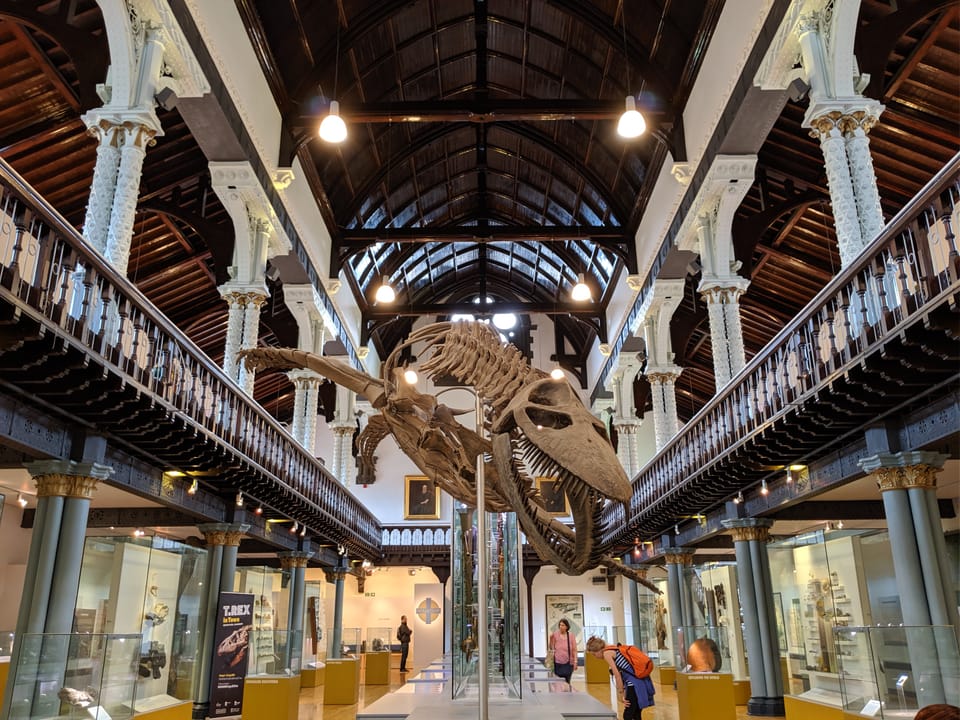

Gauging whether or not human knowledge work and learning is “useful” has become a lightning rod on social media. However, I think there is a profound value in asking this, if we think about useful not in capitalist terms, but in terms of service to our communities and to humanity. Not about being transactional, but about being reciprocal. We should care about giving eight year olds something to wonder at, we should care also about what tools we give them that will be useful for them for the rest of their lives. We should care about the kind of tradeoffs they are weighing, the dangers they are trying to hide from, like a T-Rex that will see you when you move.

I have also found this to be an important tactic for introducing humanistic narratives to people in tech. Why care about belonging? Because it is fundamentally useful. It lets us predict a huge slice of the variance in developer productivity. Why care about psychological affordances around teams? Because it is useful. It lets us predict where we will find more effective teams and design for them. Put me in any empirical bake-off for software teams in the world. I do not feel afraid, because just like I know about evolution and gravity, I know about theories of psychology that help us make sense of all the trace measures we’re seeing. I can see individual bones not as dragons sewn by a malevolent devil to fool us, but as a fossil record. The only devils I believe in anymore are here.

Lest you think I am saying changing our beliefs is easy, let me tell you I am not saying it’s easy at all. It is one of the hardest things I’ve ever done even when I was the only person I had to convince. For many years during college I experienced the disjointed splintering of my mental models, and the only way past was through. It is extraordinary that I could go on to not just do a PhD on a science campus, learning to read evidence and weight research in ways I had never seen done, but also experience the joy of an astronomy class I took for fun, the joy of a hiking trip where I learned about geology, the thousand of tiny little fractal joys that resulted from understanding a foundational theory like evolution. First it broke my mind, and made me ashamed of what I didn’t know, and then it repaired it. All because I sat with that discomfort in the university library, which I would describe as feeling like someone who had walked into the basement of their house and discovered that they had been living inside of black mold. I could’ve run away from it and I understand, intimately, why people do. It hurts. But I didn’t, because inside of me there was also that little kid turning pages of the world atlas trying to piece things together. I couldn’t let her down.

Last summer, we dealt with texts from friends closing down their labs or losing their lab jobs, and my wife grappled with the grief of having her incredibly successful STEM equity program–which funded science jobs and gave community college transfer students years of support, leading to both their own personal opportunities but also tremendous economic benefit to their communities–attacked by the highest authorities in our nation. I also saw this post and story, which has sat with me:

As scientific things still do, this moved me. Because of my childhood and because of everything I changed, I always feel different from most of the people I encounter in my life now but even different is a thing we can think about scientifically. Extremophiles don’t just exist, they are fundamentally and incredibly useful. Perhaps some of us are extremophiles, who have lived in harsh environments, or survived unsurvivable disruptions, and we are coming back to the rest of humanity or stumbling forward toward the next generations, glowing with strange discoveries. We do not know where it is all going, but we have to keep going. Science is not a thing but an action, and taking action is anti-nihilistic. It is believing that scientific questions matter, like your wonder and your hope that dinosaurs were real. It is easy to think that safe, stable, enormously resourced and untroubled science is the only way humanity gets to do it. And indeed, we lose a lot when we lose that. But most of my experience with science is with its contribution to the edge. So I believe science can also be an extremophile. It will not look the same, but there might be something unbearably precious that we find.

After I rewrote my understanding of life, I went to the Field Museum in Chicago where I got to see Lyuba, a baby mammoth from 42,000 years ago. I went alone, as I often do to museums, so that I can stand in rooms with baby mammoths and feel overwhelmed in a way that few of the other people in the room understand. I was able to receive that information, because I had made my mind something that could look at the world and see it better. So I could see that she existed, once upon a time in a very different environment, and so do I now in my particular environment that seems sometimes like it might never change, but here we are on the same planet.

Member discussion